Raising the minimum wage leads to slower job and wage growth for younger, low-wage workers

Before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, a host of cities, counties, and states moved to raise the minimum wage. Proponents argued that a higher minimum wage was needed to provide workers with enough income to afford a living wage — the amount required to maintain a normal standard of living. They viewed an increase in the minimum wage as an economic stimulus of sorts, placing more disposable income in the hands of low-income earners. Their hope is that a wage increase would help to lower employee turnover and reduce training costs. Critics claim that a higher minimum wage results in lower employment and reduced hours for existing employees. They believe an increased minimum wage creates a powerful incentive for large employers to automate jobs (witness the kiosks at McDonald’s), while driving companies with low profit margins out of business. Furthermore, they point to a lack of evidence that minimum wages are effective at reducing overall poverty rates or poverty rates among workers.

Amidst this debate, the W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a private, not-for-profit, non-partisan, independent research organization that has studied policy-related issues of employment and unemployment since 1945, states that recent working papers indicate “the pass-through effect of minimum wage increases on prices is smaller than previously thought; small raises in the minimum wage lead to slower wage growth for low-wage workers; and that the minimum wage reduces job growth over a period of several years with the effects being strongest for younger workers and for those in industries with a higher proportion of low-wage workers.”

Local and State Minimum Wage Ordinances

Most initiatives to raise the minimum wage are at the local and state level.

Leading the charge is Seattle at $16 per hour for large employers and $15 per hour for small companies. Seattle is joined by Montgomery County, Maryland; New York City; and Washington, D. C., which have established a minimum wage of $15 per hour (effective January 1, 2020). The University of California-Berkeley Labor Center’s Inventory of U.S. City and County Minimum Wage Ordinances reveals that local governments with minimum wage ordinances are highly concentrated in eight blue states — California (36), New Mexico (5), Illinois (2), Maine (2), Maryland (2), Minnesota (2), Colorado (1), Washington (1) — and the District of Columbia.

The Economic Policy Institute Minimum Wage Tracker indicates that 27 states and the District of Columbia have changed their minimum wage law since 2014 (along with their current minimum wage and sub-minimum tipped wage: Alaska ($10.19/$10.19), Arizona ($12.00/$9.00), Arkansas ($10.00/$2.63), California ($13.00/$13.00), Colorado ($12.00/$8.98), Connecticut ($11.00/$6.38), Delaware ($9.25/$2.23), Hawaii ($10.10/$10.10), Illinois ($10.00/$6.00), Maine ($12.00/$6.00), Maryland ($11.00/$3.63), Massachusetts ($12.75/$4.95), Michigan ($9.65/$3.67), Minnesota ($10.00/$10.00), Missouri ($9.45/$4.73), Nebraska ($9.00/$2.13), Nevada ($9.00/$9.00), New Jersey ($11.00/$3.13), New Mexico ($9.00/$2.35), New York ($11.80/$7.85), Oregon ($12.00/$12.00), Rhode Island ($10.50/$3.89), South Dakota ($9.30/$4.65), Vermont ($10.96/$5.48), Washington ($13.50/$13.50), Washington, D. C. ($15.00/$5.00), and West Virginia ($8.75/$2.63).

Seven states have no minimum wage law or have in place a minimum wage below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour — Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wyoming. The federal minimum wage applies in all of these states.

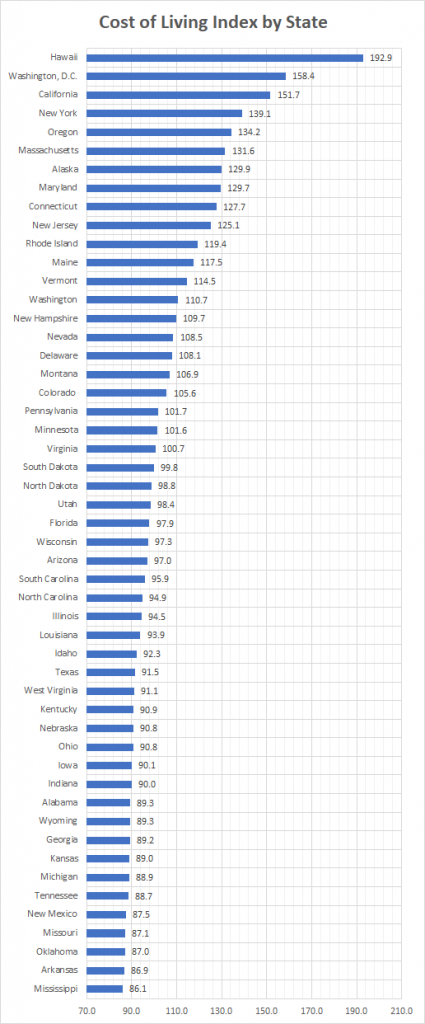

Cost of living plays an important role in creating industry and region differentials in minimum wage rates. For example, Oregon’s minimum wage law establishes a separate minimum wage rate for the Portland Urban Growth Boundary area and designated non-urban counties. New York law establishes separate minimum wage rates for New York City, suburban counties, and the rest of the state. Simultaneously, New York’s minimum wage law allows for variations by industry. The fast-food industry started at $10.50 in New York City and $9.75 for the rest of the state, both gradually rising to $15 per hour over a period of several years.

Another common feature is indexing for inflation, which calls for making annual adjustments in the minimum wage based on changes in the Consumer Price Index (states are measured against the national average, which is set at 100). This occurs in eighteen different states and the District of Columbia.

Source: World Population Review, 2020

This hodge-podge of higher minimum wages is a reflection of several factors, not least of which are cost of living and political philosophy. It is no coincidence that the highest minimum wages are most often found in jurisdictions with the highest costs for housing, food, healthcare, and other expenses (see chart above). Nor is it a coincidence that the most expensive jurisdictions to live in are Democratic strongholds.

National Minimum Wage

Several groups advocate for raising the national minimum wage to $15 per hour — Campaign for America’s Future, Economic Policy Institute, FairShare, Interfaith Worker Justice, Let Justice Roll Living Wage Campaign, National Employment Law Project, Partnership for Working Families, Reclaim the American Dream, Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, and United for a Fair Economy. These proponents are primarily concerned about providing a living wage for workers, reducing poverty, and wage inequality.

Opposing their efforts are major business organizations such as the National Association of Manufacturers, National Federation of Independent Business, National Restaurant Association, National Retail Federation, and U.S. Chamber of Commerce. They argue that a national minimum wage of $15 per hour leads to increased labor costs and tough choices, causing employers to reduce jobs, reduce hours, or reduce benefits.

Lost in our political discourse are the implications of a one-size-fits all approach that creates unintended consequences for the U.S. and its tapestry of economically diverse states. It’s one thing to implement a $15 minimum wage for low-wage workers in Hawaii, which has a cost of living index of 192.9; another thing entirely to implement a $15 minimum wage in Mississippi, where the cost of living index is 86.1* The impact on lower cost of living states, their industries, and their employees, is broader and far more disruptive.

Weighing in on the discussion is the Congressional Budget Office, which estimates that raising the minimum wage to $15 from its current $7.25 could cost 1.3 million jobs, while increasing wages for 17 million workers.

Despite the state and region differentials in minimum wage, and the prospect of permanent job loss, the Democratic-controlled U.S. House of Representatives passed H. R. 582 – Raise the Wage Act to boost the national minimum wage to $15 per hour in a recorded vote of 231-199. The bill also eliminates the separate minimum wage requirements for disabled, tipped and newly-hired employees (under 20 years of age), bringing them into line with regular employees over a 7-year period. Political observers believe the Senate is unlikely to take up the bill, and President Trump has indicated he’s prepared to veto the legislation.

Minimum wage increases generate mixed outcomes. A higher minimum wage increases worker purchasing power and stimulates consumer demand. On the flip side, a higher minimum wage discourages employers from hiring low-skill, low-wage workers, which leads to slower wage growth — particularly for younger workers — and creates an incentive to replace human labor with automation technology. To a large extent, the gains and losses attributed to a higher minimum wage offset one another.

Perhaps minimum wage federalism offers a better answer.

Why Federalism Matters opens with this statement:

“What do we want from federalism?” asked the late Martin Diamond in a famous essay written thirty years ago. His answer was that federalism — a political system that permits a large measure of regional self-rule — presumably gives the rulers and the ruled a “school of their citizenship,” “a preserver of their liberties,” and “a vehicle for flexible response to their problems. These features, broadly construed, are said to reduce conflict between diverse communities, even as a federated polity affords inter-jurisdictional competition that encourages innovations and constrains the overall growth of government” (The Brookings Institution, 2005).

Democrats and other proponents of a higher national minimum wage of $15 per hour are pushing for a level of forced uniformity that ignores the dramatic effects that a “cookie-cutter” minimum wage policy has on employers and workers in different states across the country. As such, state governments and municipalities should be given the flexibility to continue experimenting with their own minimum wage policies. This allows other jurisdictions to learn from their successes and failures.

As an added benefit, decentralizing the minimum wage issue enables the federal government to focus on more important fiscal obligations. For example, COVID-19 has pushed the 2020 National Deficit to $2.74 trillion through June. Second-tier financial issues, like the minimum wage, should be delegated to lower levels of government.

If reducing poverty is the desired policy outcome, there is compelling evidence that the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a far more effective tool:

“Each one percent in a state supplement to the federal EITC reduces poverty rates by one percent. (It also provides an incentive to seek employment, since the credit can only be claimed on earned income)” (Economic Policies Institute, 2020).

Wouldn’t it be nice if the U.S. Congress chose to get the federal government’s fiscal house in order before attempting to dictate to the people about minimum wage policy? Wouldn’t it be nice if the U.S. Congress worked smarter, and not just harder?

*Editor’s Note: A worker earning $15 per hour in Honolulu, Hawaii is equivalent to earning $6 per hour in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, once allowances are made for the difference in cost of living.