Affordable Housing is a Critical Part of Economic Development

Most economic developers occupy a privileged position in the community. They get to rub shoulders with academic administrators, corporate executives, government officials, media representatives, and other influencers. They might serve on the board of directors for a local charitable organization, or take a leadership role in philanthropic fundraising for arts and cultural programs. What doesn’t always get their attention are current trends in income and economic inequality, the growing divide between the “haves” and “have-nots,” and what they can do about it.

A case in point is affordable housing.

Lara Fitts, President and CEO of the Greater Richmond Partnership, writes:

“A few months ago, I was talking with a fellow economic development professional who asked me, why I cared about affordable housing because in his words, ‘affordable housing isn’t economic development.’ In his view, economic development is meant to help companies facilitate job creation, enhance the community’s tax base, and provide opportunities for increasing household incomes. However, what happens when a community is so successful in its economic development efforts that the supply of housing decreases and prices escalate so quickly that jobs and income growth don’t keep up?”

The truth of the matter is that affordable housing is a critical part of economic development.

Quality of Life

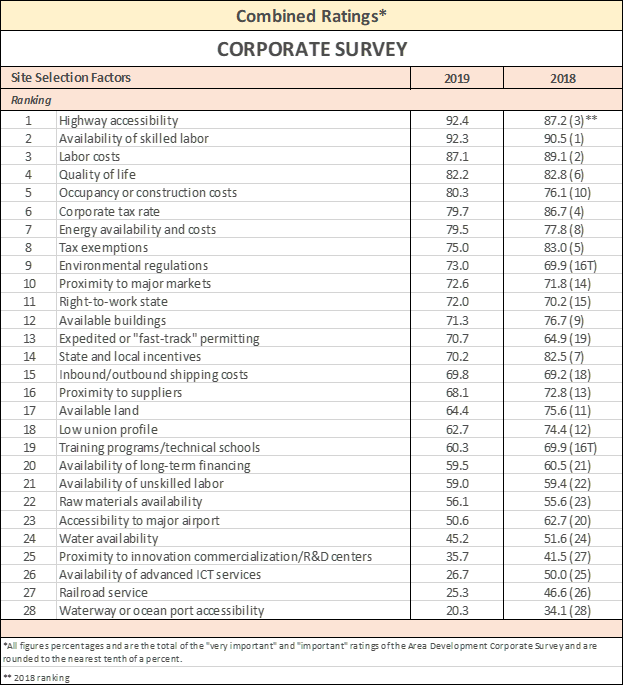

To ensure they’re able to attract skilled workers, companies are increasingly interested in localized quality of life factors in the site selection process. In Area Development’s “34th Annual Survey of Corporate Executives and 16th Annual Consultants Survey,” quality of life ranked 4th, behind only highway accessibility, availability of skilled labor, and labor costs and ahead of 24 other site location factors like state and local incentives and accessibility to a major airport. Baked into the quality of life recipe is a key ingredient — an employee’s ability to secure adequate housing.

Affordable Workforce Housing

Consider for a moment how housing affects a business’s competitiveness strategy — indeed, a region’s competitiveness — in terms of attracting and retaining talent. When employees can’t afford to live near their place of work, employers have to spend more money on relocation expenses, wages, and face higher turnover rates. Where employees choose to live is also impacted by the work situation of their spouse, partner or significant other; commute times (the average is 25-35 minutes); neighborhood characteristics; schools; and safety.

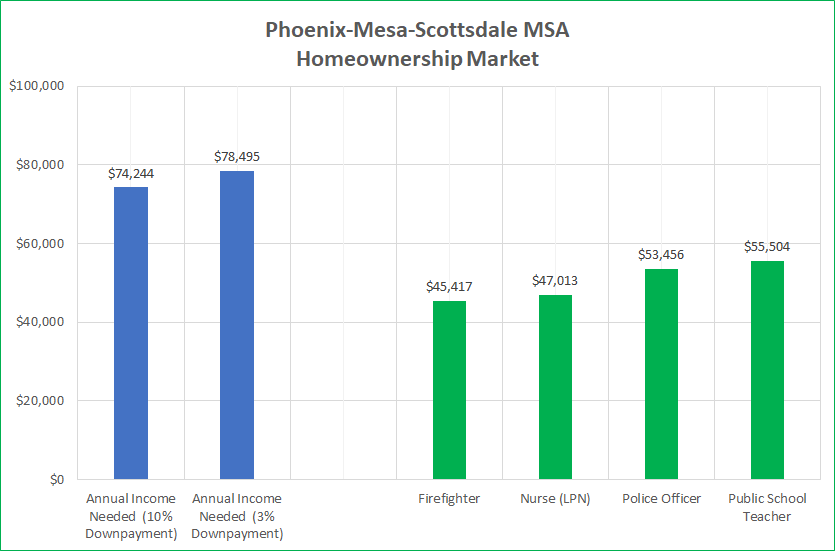

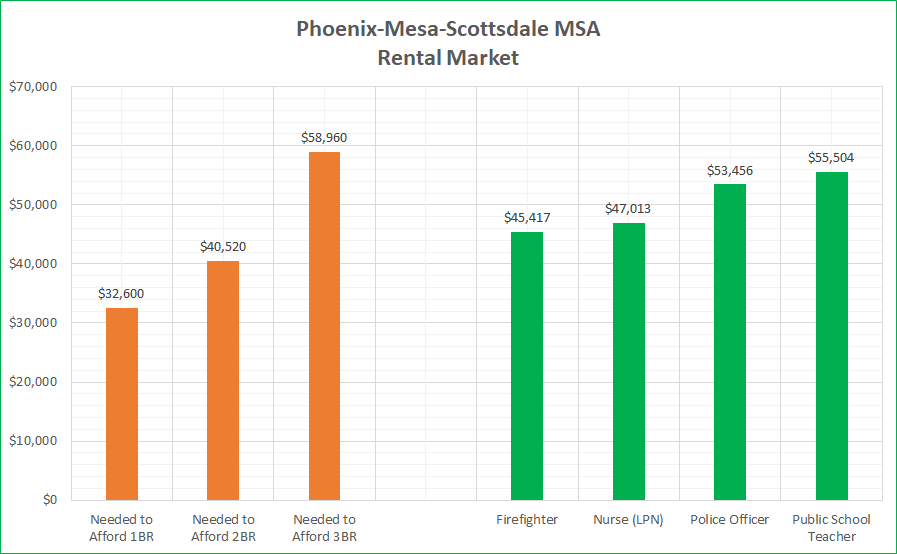

Now ask yourself, when you’re considering a job offer, how long does it take before you start to factor in salary, housing options, and commute time? Then, for the sake of argument, imagine that you have accepted a position on the same pay scale as an “essential worker” — police officer, firefighter, nurse (LPN), or public school teacher. Your income falls within 60 to 120 percent of area median income. Mortgage lenders impose a limit of 28 to 30 percent of household income for principle, interest, taxes, and insurance (PITI). Given these parameters, what are your housing options?

The homeownership market appears to be out of reach — aside of being able to tap into a second income or some other type of financial assistance. This assumes prospective homeowners are looking to buy a medium-priced home in the Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale MSA, which has an affordability index of 6 (on a scale of 1 to 10; 1 is the most affordable, 10 is the least affordable), per Kiplinger (2020).

This leads a prospective employee to the rental market, where a 1- or 2-bedroom apartment or other residential rental property becomes financially palpable. Even under these more favorable conditions, the 3-bedroom option is too expensive.

The State of the Nation’s Housing

The Joint Center of Housing Studies of Harvard University’s report, “The State of the Nation’s Housing 2019,” provides an overview of pre-coronavirus pandemic housing trends. Their researchers found that despite household growth returning to a more normal pace during the past decade, housing construction wasn’t able to maintain the same rate of progress, keeping pressure on home prices and rents and eroding affordability.

Factors contributing to the continued shortfall in housing supply include relatively weak household growth since the Great Recession, with the national vacancy rate for both owner-occupied and rental units falling to 4.4 percent, its lowest point since 1994. Influencing the slow construction recovery is a wariness on the part of builders and lenders, who haven’t forgotten how difficult it was to work through the housing boom of the early 2000s, which created an excess supply of homes. Labor shortages, complicated by an economy nearing full employment, and the rising costs of land and materials made it unprofitable for developers to build for the middle market. Instead, home builders chose to build in the higher end of the housing market, where they’re able to cover their expenses. Regulatory restrictions on higher-density development and not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) opposition made it even more challenging to provide affordable housing products.

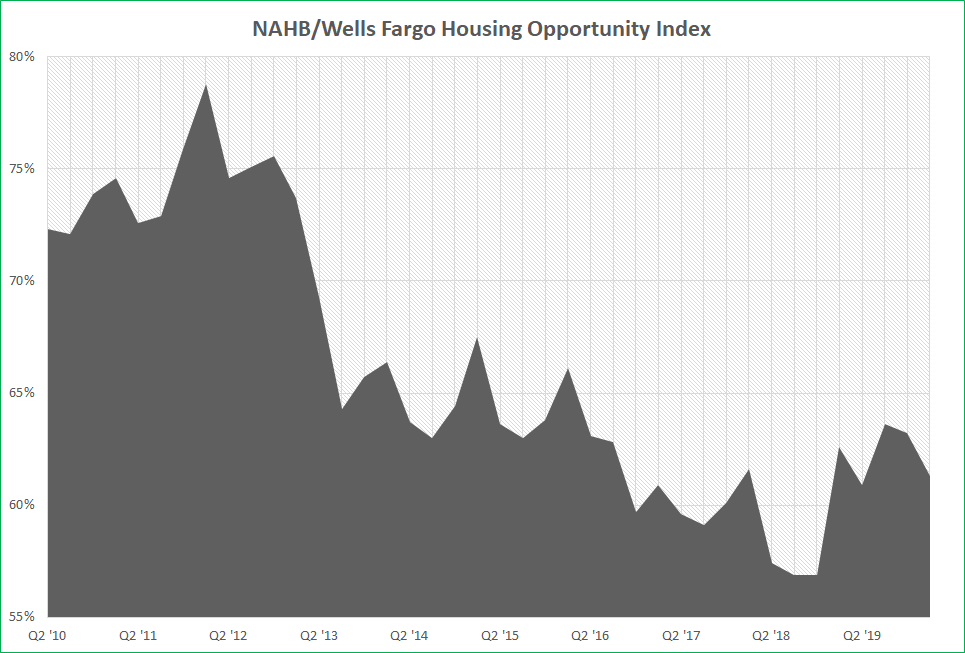

In terms of housing income and affordability, cost burdens have continued to move up the income scale. National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) economists have calculated that more than half of U.S. households — 63 million to be precise — are unable to afford a $250,000 home. In a similar vein, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis determined that national house price indices have outpaced increases in per capita income and inflation since 2012.

One of those indices is the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index, which measures the share of homes that would have been affordable to a family earning the average median income, based on standard mortgage underwriting criteria. The index utilizes two major components — income and housing cost — and reveals how housing costs have worsened in recent years.

City of Dallas

The City of Dallas (pop. 1,343,573) — our nation’s ninth-largest municipality — has Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization, the Office of Economic Development, and Planning and Urban Design organized under the direction of Michael A. Mendoza, Chief of Economic Development and Neighborhood Services. This underscores the interdependence that exists between community development, economic development, and planning.

Dallas’ Housing Policy Toolkit consists of the following:

Market Value Analysis

The Market Value Analysis (MVA) is a data-driven tool that helps residents and policymakers analyze the local real estate market at a census block level. It is built on local administrative data and validated by local experts. This analysis was prepared by The Reinvestment Fund. Public officials and private actors utilize the MVA to more precisely target intervention strategies in weak markets and support sustainable growth in stronger markets.

Nine market types are identified on a color-coded spectrum of residential strength or weakness, along with the number of Census Block Groups in each market type. Included are multiple tabs for key indicators — median sales price, sales price variance, percent owner occupied, percent vacant homes, percent new construction units, percent rehabilitation units, percent foreclosure filings, and percent code violations.

The MVA also provides tabs to other geographic data for mapping purposes — reinvestment areas, bond projects, City land, tax increment finance (TIF) districts, public improvement districts (PIDs), New Markets Tax Credits, Opportunity Zones, Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) eligible areas, R/ECAP areas, DISD and RISD elementary schools, and DISD and RISD middle schools.

Comprehensive Housing Policy

Dallas’ Comprehensive Housing Policy is guided by the Market Value Analysis and identifies a housing shortage of approximately 20,000 units. Six out of ten families are housing cost-burdened (spend more than 30 percent of income on housing), making it difficult to build asset wealth and break multi-generational cycles of poverty.

Three overarching goals drive the policy: (1) Create and maintain affordable housing units throughout Dallas; (2) Promote greater fair housing choices; and 3) Overcome patterns of segregation and concentrations of poverty through incentives and requirements. Various housing and financial assistance programs, ranging from creation of a Housing Trust Fund to the adoption of an ordinance amendment that allows homeowners to build and rent Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) are contemplated in the housing policy.

Strategic Economic Development Plan

Complementing Dallas’ Housing Policy Toolkit is the Draft Strategic Economic Development Plan (2019). During the stakeholder engagement phase, respondents to an online residential survey identified affordable housing as a leading issue (ranked #3 behind quality of public schools and City infrastructure). The market assessment phase determined that Dallas has the second largest share of homeowners whose monthly owner costs are 30 percent or greater than household income, when compared to Chicago, Atlanta, Denver, Phoenix, Austin, Houston, San Antonio, and Fort Worth.

The Strategic Action Plan phase outlines four overarching goals, one of which is “Opportunity for All: An Equitable and Inclusive Economy.” Under this goal, interested parties will find “Strategy #1: Revitalize South Dallas/Southern Dallas,” that devotes a significant amount of attention to “Affordable Housing.” This is a best-practice example of how affordable housing policies are harmonized with Dallas’ economic development initiatives.

The link between affordable housing and economic development is stronger than many practitioners might realize. Too often, the creation and implementation of a diversified housing program is viewed as something that has or should be relegated to a separate community development or human services department. As a result, limited thought is given to the impact of affordable housing on local economic development. However, the relatively high ranking of quality of life in site selection, the prominence of affordable housing in quality of life assessments, and the high priority that citizens place on having a safe and decent place to live should give economic developers pause for thought.

Economic developers have the privilege of attending high-profile groundbreaking ceremonies for assisted corporate locates and other business projects. Those on the guestlist often read like a “Who’s Who” list of C-level executives, elected officials, and other dignitaries; people who reside in the top five percent income stratum. Behind the scenes are the assembly line laborers, call center operators, construction journeymen, distribution warehouse specialists, public sector “essential workers,” and retail associates who reap much smaller financial rewards. We owe it to them to make sure they share in the community’s economic growth.

Making affordable housing a reality, especially in locations that are close to work, maximizes their ability to build wealth.

###